The NotPetya ransomware that encrypted and locked thousands of computers across the globe yesterday and today is, in reality, a disk wiper meant to sabotage and destroy computers, and not ransomware. This is the conclusion of two separate reports coming from Comae Technologies and Kaspersky Lab experts.

Experts say that NotPetya — also known as Petya, Petna, ExPetr — operates like a ransomware, but clues hidden in its source code reveal that users will never be able to recover their files.

This has nothing to do with the fact that a German email provider has shut down the NotPetya operator’s email account. Even if victims would be able to get in contact with the NotPetya author, they still have no chance of recovering their files.

NotPetya never bothers to generate a valid infection ID

This is because NotPetya generates a random infection ID for each computer. A ransomware that doesn’t use a command-and-control server — like NotPetya — uses the infection ID to store information about each infected victim and the decryption key.

Because NotPetya generates random data for that particular ID, the decryption process is impossible, according to Kaspersky expert Anton Ivanov.

“What does it mean? Well, first of all, this is the worst-case news for the victims – even if they pay the ransom they will not get their data back. Secondly, this reinforces the theory that the main goal of the ExPetr attack was not financially motivated, but destructive,” said Ivanov.

MFT file is unrecoverable

Kaspersky’s discovery was also reinforced by a separate report released by Comae Technologies researcher Matt Suiche, who found a totally different flaw but reached the same conclusion.

In his report, Suiche describes a faulty sequence of operations that would make it impossible to recover the original MFT (Master Tree File), which NotPetya encrypts. This file handles the location of files on a hard drive, and with this file remaining encrypted, there’s no way to know where each file is where on an affected computer.

“[The original] Petya modifies the disk in a way where it can actually revert its changes. Whereas, [NotPetya] does permanent and irreversible damages to the disk,” Suiche said.

NotPetya was designed for mayhem, not making money

The idea that NotPetya did not follow regular ransomware rules was first proposed by threat intelligence expert The Grugq, in a report published yesterday.

“The real Petya was a criminal enterprise for making money. This [NotPetya] is definitely not designed to make money,” The Grugq said. “This is designed to spread fast and cause damage, with a plausibly deniable cover of ‘ransomware.’”

What needs to be made clear is that NotPetya is not a disk wiper per se. It does not delete any data but simply makes it unusable by locking files and throwing away the key.

“In my book, a ransomware infection with no possible decryption mechanism is equivalent to a wiper,” J. A. Guerrero-Saade, security researcher for Kaspersky Lab told Bleeping Computer today via email. “By disregarding a viable decryption mechanism, the attackers have displayed a complete disregard for long-term monetary gain.”

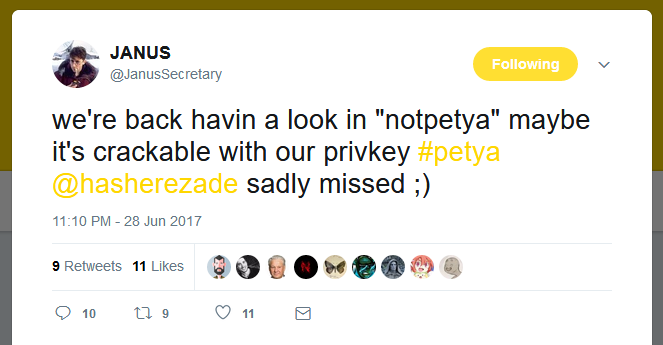

Furthermore, in a tweet sent out today, the author of the original Petya also made it clear NotPetya was not his work, dispelling any rumors that this was a Petya offshoot.

He, in fact, is the second ransomware author that had to say this, after the author of the AES-NI ransomware said in May he did not create the XData ransomware, which was also used in targeted attacks against Ukraine. Furthermore, both XData and NotPetya used the same distribution vector, the update servers of a Ukrainian accounting software maker.

Signs with big bright blinking lights point to the theory that someone is hijacking known ransomware families and using them to attack Ukrainian users.

Hiding wipers in ransomware has become common practice

While this sounds sneaky, it’s actually been done before. Attackers with a hidden agenda that are posing as mundane cyber-criminals and hiding disk wipers as ransomware is not a new tactic. It’s actually a trend.

This past fall and winter we’ve seen reports of disk wipers getting “ransomware components” so they could pass on as ransomware infections and avoid the scrutiny of incident responders. This happened with the Shamoon and KillDisk malware families, both tools known for their disk-wiping abilities. Furthermore, even industrial malware is getting disk wiping features.

With NotPetya’s reclassification as a disk wiper, experts can easily put the malware in the category of cyber-weapons, and analyze its effects from a different perspective.

With the point of origin and most victims residing inside its borders, it’s pretty obvious that Ukraine was the victim. There is no palpable evidence to point the finger towards an attacker, but Ukrainian officials had already blamed Russia, who they accused in the past of several other cyber-incidents going way back to 2014.

The consensus on NotPetya has shifted dramatically in the past 24 hours, and nobody would be wrong to say that NotPetya is on the same level with Stuxnet and BlackEnergy, two malware families used for political purposes and for their destructive effects. Evidence is clearly mounting that NotPetya is a cyber-weapon and not just some overly-aggressive ransomware.