A cyber mercenary that “ostensibly sells general security and information analysis services to commercial customers” used several Windows and Adobe zero-day exploits in limited and highly-targeted attacks against European and Central American entities.

The company, which Microsoft describes as a private-sector offensive actor (PSOA), is an Austria-based outfit called DSIRF that’s linked to the development and attempted sale of a piece of cyberweapon referred to as Subzero, which can be used to hack targets’ phones, computers, and internet-connected devices.

“Observed victims to date include law firms, banks, and strategic consultancies in countries such as Austria, the United Kingdom, and Panama,” the tech giant’s cybersecurity teams said in a Wednesday report.

Microsoft is tracking the actor under the moniker KNOTWEED, continuing its trend of terming PSOAs using names given to trees and shrubs. The company previously designated the name SOURGUM to Israeli spyware vendor Candiru.

KNOTWEED is known to dabble in both access-as-a-service and hack-for-hire operations, offering its toolset to third parties as well as directly associating itself in certain attacks.

While the former entails the sales of end-to-end hacking tools that can be used by the purchaser in their own operations without the involvement of the offensive actor, hack-for-hire groups run the targeted operations on behalf of their clients.

The deployment of Subzero is said to have transpired through the exploitation of numerous issues, including an attack chain that abused an unknown Adobe Reader remote code execution (RCE) flaw and a zero-day privilege escalation bug (CVE-2022-22047), the latter of which was addressed by Microsoft as part of its July Patch Tuesday updates.

“The exploits were packaged into a PDF document that was sent to the victim via email,” Microsoft explained. “CVE-2022-22047 was used in KNOTWEED related attacks for privilege escalation. The vulnerability also provided the ability to escape sandboxes and achieve system-level code execution.”

Similar attack chains observed in 2021 leveraged a combination of two Windows privilege escalation exploits (CVE-2021-31199 and CVE-2021-31201) in conjunction with an Adobe reader flaw (CVE-2021-28550). The three vulnerabilities were resolved in June 2021.

The deployment of Subzero subsequently occurred through a fourth exploit, this time taking advantage of a privilege escalation vulnerability in the Windows Update Medic Service (CVE-2021-36948), which was closed by Microsoft in August 2021.

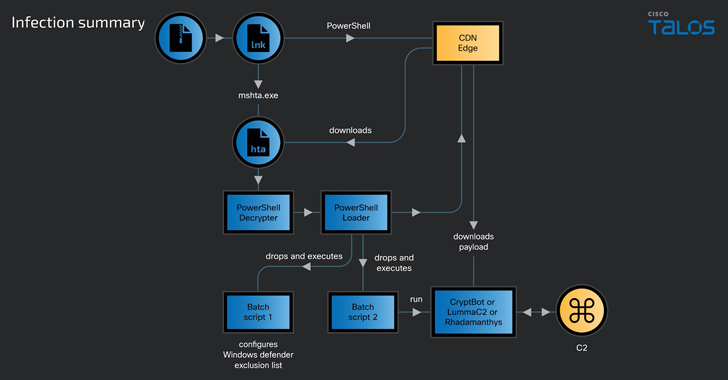

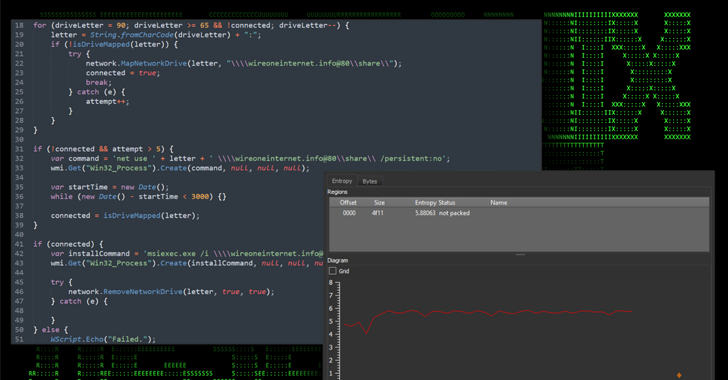

Beyond these exploit chains, Excel files masquerading as real estate documents have been used as a conduit to deliver the malware, with the files containing Excel 4.0 macros designed to kick-start the infection process.

Regardless of the method employed, the intrusions culminate in the execution of shellcode, which is used to retrieve a second-stage payload called Corelump from a remote server in the form of a JPEG image that also embeds a loader named Jumplump that, in turn, loads Corelump into memory.

The evasive implant comes with a wide range of capabilities, including keylogging, capturing screenshots, exfiltrating files, running a remote shell, and running arbitrary plugins downloaded from the remote server.

Also deployed during the attacks were bespoke utilities like Mex, a command-line tool to run open source security software like Chisel, and PassLib, a tool to dump credentials from web browsers, email clients, and the Windows credential manager.

Microsoft said it uncovered KNOTWEED actively serving malware since February 2020 through infrastructure hosted on DigitalOcean and Choopa, alongside identifying subdomains that are used for malware development, debugging Mex, and staging the Subzero payload.

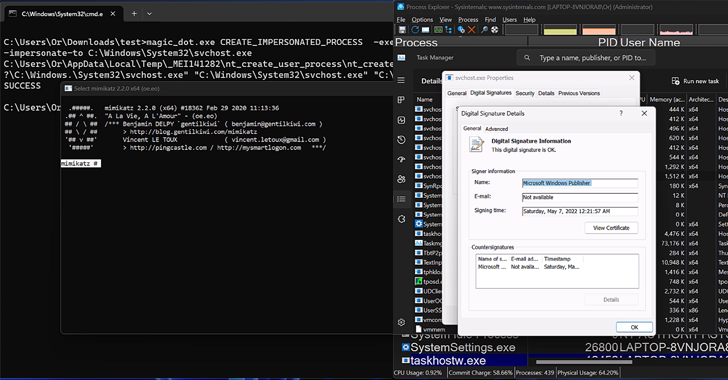

Multiple links have also been unearthed between DSIRF and the malicious tools used in KNOTWEED’s attacks.

“These include command-and-control infrastructure used by the malware directly linking to DSIRF, a DSIRF-associated GitHub account being used in one attack, a code signing certificate issued to DSIRF being used to sign an exploit, and other open-source news reports attributing Subzero to DSIRF,” Redmond noted.

Subzero is no different from off-the-shelf malware such as Pegasus, Predator, Hermit, and DevilsTongue, which are capable of infiltrating phones and Windows machines to remotely control the devices and siphon off data, sometimes without requiring the user to click on a malicious link.

If anything, the latest findings highlight a burgeoning international market for such sophisticated surveillance technologies to carry out targeted attacks aimed at members of civil society.

Although companies that sell commercial spyware advertise their wares as a means to tackle serious crimes, evidence gathered so far has found several instances of these tools being misused by authoritarian governments and private organizations to snoop on human rights advocates, journalists, dissidents, and politicians.

Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG), which is tracking over 30 vendors that hawk exploits or surveillance capabilities to state-sponsored actors, said the booming ecosystem underscores “the extent to which commercial surveillance vendors have proliferated capabilities historically only used by governments.”

“These vendors operate with deep technical expertise to develop and operationalize exploits,” TAG’s Shane Huntley said in a testimony to the U.S. House Intelligence Committee on Wednesday, adding, “its use is growing, fueled by demand from governments.”