If you thought that the problem of tech support scams was disappearing, think again, says Josep Albors and David Harley.

If you asked most people what they believe to be the most prevalent form of threat right now, they’d almost certain say ‘ransomware’. However, my colleague Josep Albors has come to a surprising conclusion in his Spanish language blog Fake technical support is the most detected threat in Spain during January. While the data on which he drew indicates that Spain leads the field in detections of HTML/FakeAlert, several other countries (including the UK and France) are seeing detections in surprisingly large quantities.

The following is a very free translation of Josep’s article with some commentary from me. Any errors in translation are down to me.

It’s not all about ransomware

Malicious software (malware) and ransomware in particular are among the most notorious threats at the moment, and capable of causing a great deal of harm to their victims, whether it’s financial loss or the loss of valued data. Nevertheless, there are other threats that may be less damaging – at any rate to targeted organizations, which tend to be required to pay larger ransoms than random individual victims – but are by no means harmless. Even the range of weaselly nuisances that the security industry tends to categorize as ‘Possibly Unwanted’ are sometimes intrusive enough to impact seriously on a computer/device user’s online experience. While messages, phone calls and web pages used to execute fraud such as support scams are no less criminal in intent than ransomware, though they may in most cases cause less damage.

That said, a support scammer who has succeeded in luring victims into giving him access to their systems has often proved more than happy to trash that system if the victim isn’t sufficiently compliant.

Help with the problem you didn’t know you had

Support scams are by no means new: I first started writing about them in 2010 or thereabouts, as did Josep. In those days, the problem was mostly confined to cold calls (unsolicited telephone calls) made to more-or-less random English-speaking computer users. In due course, these calls got to be supported by a dubious infrastructure of websites and Facebook pages offering ‘help’ to users of specific products. These gave the scammers the ability to point to sites marketing their apparently ‘legitimate’ services when cold-calling reluctant victims. However, they were also widely advertised through search engines so that potential victims with a genuine computer problem were likely to come across these less-than-genuine services and phone numbers when searching for a source of assistance.

Irritatingly, we have seen many instances of such sites offering ‘support’ for specific legitimate products where the vendor already offered real support via their own pages. Though we have also seen isolated instances where a vendor outsourced support to companies who misused their position of trust to press their own advantage using classic support scam techniques.

Cold-calling to SEO to fake alerts

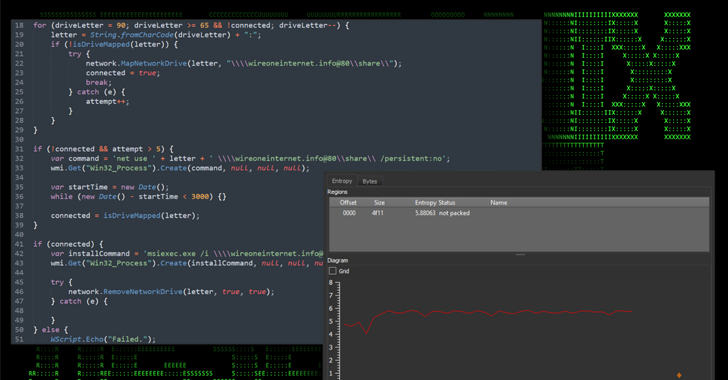

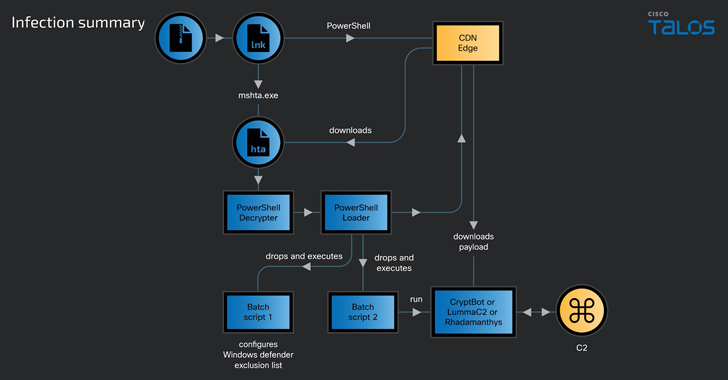

In recent years, cold-calling and basic SEO (Search Engine Optimization) exploitation has to a large extent been augmented or supplanted by the use of various highly proactive methods – including what amounts to malware – of luring the victim into actively ringing the ‘support line’.

Consider, for instance, a malicious program that masquerades as an installer for Microsoft’s own Security Essentials program. Hicurdismos generated a fake Blue Screen of Death (BSoD) including a ‘helpline number’: so it was essentially a malware-aided tech support scam, spread by drive-by-download, and taking steps – such as hiding the mouse cursor and disabling Task Manager – to make its payload look like a serious system issue.

However, most attacks take the form of fake system alerts that ‘warn’ the victim of a virus or similarly frightening issue and provide a ‘support’ telephone number. (Sometimes these use a similar fake system crash to those used by some bottom-feeder ransomware gangs.)

When a victim is frightened into ringing one of these numbers, he or she is connected to a scammer who uses similar techniques to the cold-call scammers of yore to trick the victim into thinking that they have a real problem, and that the scammer can really fix it. Though once the scammer has direct contact with victims, the tricks they use against Windows users are much the same deceptive gambits as those used for years:

- To ‘prove’ that the scammer has information specific to the victim’s system (e.g. the CLSID gambit)

- And to ‘prove’ that there is a real problem (as proven by misrepresenting the output of standard Windows utilities).

Telemetry and statistics

There is a disadvantage to this trend, however, as far as the scammer is concerned. It’s obviously easier for security companies to track scam URLs that pop up deceptive messages than it is to track random phone calls. I don’t track our telemetry regularly at this point in my career, but Josep has noted that in recent months, we have seen a considerable increase in the number of Spanish users who have received a call or seen an alert on their system urging them to call a ‘support’ phone number. He continues:

If we look at the evolution of this threat we see that until July 2016 it was hardly ever reported in Spain. However, from that date, the number of detections has grown continuously, and this type of attack at times now accounts for almost 50% of threats detected in Spain according to ESET’s monthly monitoring system Virus Radar.

This dramatic increase corresponds to a change of strategy by the offenders behind this scam. Originally it was the scammers who cold-called their potential victims, posing as technicians or from Microsoft another trusted, legitimate company. However, this strategy was augmented by another one which, given the figures from VirusRadar, seems to be giving them better results.

This newer strategy is to display alert messages on the user’s system. In this way, the scammers await the calls of their victims, and from certain investigations we have performed, it seems that the scammers’ switchboards are well prepared to receive victims’ calls in large volumes. Figure 2 shows an example in (mostly) Spanish, taken from Josep’s article, but there are plenty of English-language examples like the ones I cited here and the ones shown at Virus Radar.

If the potential victim is tricked into calling the number shown in such an alert, he is already halfway to allowing a so-called technician to install a remote control application onto his system. From there, it is usual for the scammer to open a system application such as the Windows Event Viewer to try to convince the victim that his system is in danger and that he needs to pay the ‘support service’ in order to fix the non-existent problem.

An evolving threat

The increased number of detections of these cases of fake technical support among Spanish computer users indicates that the criminals are specifically targeting Spain, though it may be that they’ll move on eventually to other Spanish-speaking countries in the same way that they moved on to a range of English-speaking countries in the cold-call era, and even to countries where English isn’t the primary local language. For the moment, however, the Virus Radar prevalence map indicates that only France, the UK, Australia and New Zealand are close to the levels of detection in Spain.

Virus Radar statistics

Table 1 compares statistics for several countries over the last month.

| Spain | 37.86% |

| France | 31.24% |

| Australia | 25.39% |

| United Kingdom | 23.16% |

| Republic of Ireland | 18.66% |

| Canada | 18.6% |

| Norway | 18.34% |

| United States | 17.02% |

Table 1: Some prevalence statistics (as of 11th February 2017)

By contrast, other Spanish-speaking countries have much lower levels of detection: for instance Mexico (1.95%) and Argentina (0.1%). Perhaps these countries are not currently seen by the scammers to offer such rich pickings as European countries, where victims are charged 100 Euros and more?

So why now?

Josep’s analysis suggests that displaying fake alarms or blocking the user’s screen directly are not the only factors that have caused an increase in the number of Spanish users to be caught out by scammers. He believes that the use of PBXs and switching services with operators located in Spanish-speaking countries has also helped people think that they are actually calling an official technical support service. Earlier in the evolution of the scam, he suggests, the majority of cold-call scammers and merely read out a script. This was also true of many English-speaking cold-callers. However, because so many legitimate support services in English-speaking countries have long been outsourced to India, it took a while before people in those countries started to be automatically suspicious of anyone cold-calling with a strong Indian accent. In Spain, however, Josep suggests that callers who were not fluent in Spanish, reading from a script and burdened with a pronounced accent, were less likely to be trusted, and the majority hung up without paying attention to the false warnings.

Let’s be clear, though. Identifying a potential scammer by his or her accent has always been a weak heuristic. By the time the scam was moving away from cold-calling to malvertising, it had already been taken up in other parts of the world, including the US.

Peaks and troughs

While Josep’s figure of nearly 50% is not, according to the figures above, seen on a daily basis, analysis of the number of detections of this threat in Spain over a period of weeks shows a clear upward trend, with peaks during the week and a significant decrease at weekends.

This pattern may invite several (not necessarily mutually exclusive) speculations. Scammer activity, like malware campaigns, shows a variation of intensity over days and weeks, indicating perhaps that even criminals sometimes take the weekend off. (As I’m at present writing on a Saturday night, perhaps there is something I can learn from that.) Josep also suggests, though, that these patterns also suggest that people working for Spanish companies also access links that generate false alerts during office hours. It would be interesting to know whether there is a direct correlation to BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) usage patterns among companies in Spain, but I don’t.

Josep goes on to observe that:

The short- and medium-term problem is that criminals are not only content to cheat their victims by offering unnecessary services, often by charging for software that the victim could get for free elsewhere if he really needed to. But they also take advantage of the remote access that victims give them to their systems and devices. This may allow them to install other threats to the system such as ransomware, or to steal confidential information.

Conclusion

The security industry in general has tended not to take the tech support scam too seriously, apart from a few persistent souls who have continued to follow its evolution and keep trying to raise awareness. But evolve it does. If you thought that it was a dying issue, think again. It continues to evolve, and the scammers are not going to give it up while there are still comparatively untapped sources of potential victims. Cold-calling scammers have tended to rely on social engineering and SEO, though some of the tricks they’ve used (misrepresenting ASSOC, EventViewer, Netstat and so on), to deceive victims into thinking they have a virus problem have been quite clever. What’s more, despite our efforts to explain how they work, people are still falling for them. But more recently, the scammers have spread their nets far wider, using malicious programs and web sites, launching fake alerts from genuine sites, borrowing techniques from ransomware such as fake Blue Screens of Death (BSoDs). By way of acquiring extra (fake) credibility, there are also suspicions that they have been able to acquire customer information from legitimate sources such as service providers and IT vendors.

Still, the scammer’s main weapon is still social engineering: it’s just that if you’ve been railroaded into ringing a fake helpline, you’re already halfway to giving him access to your system, not mention your credit card. I’m going to quote myself (from an old article for ITSecurity UK, slightly edited; but many of the staples of support scamming haven’t really changed):

Fake security alerts and fake system crashes still involve two main strands of social engineering:

- Persuading you to ring a specific phone number (which real systems crashes and alerts hardly ever do)

- Persuading you to do so immediately so that you don’t notice that what appears to be a Blue Screen of Death is actually just a pop-up.

[…]

If you see some sort of pop-up message or even a Blue Screen of Death including a ‘helpdesk’ telephone number, expect the worst. If it turns out you really do have a problem, find a more reliable source in your region for a helpdesk number.

And if you have security software (why would you not have security software???) and it’s a reliable product, the chances are that if you really do have a problem, the vendor can provide you with better support than a random cold-caller or whoever is on the other end of that ‘helpline’ number.