ESET’s David Harley returns to the theme of what to do if a scammer gets a foothold on your system – people are still worried about support scams.

Note: This blog article expands on some of the content that originally appeared in a lengthy article on support scams for ITSecurity UK, and subsequently in an article for the ESET Threat Report for December 2015.

The implications of intrusion

I’m returning to the theme of what to do if a scammer actually gets a foothold on your system, because I still see a number of blog comments from people worried about the implications of such an intrusion and wondering what action they need to take. In fact, there is no single clear-cut answer to that question.

Variety is the ‘spice of scamming’

That’s because there is no single ‘support scam’, though I often see articles that describe a single type of scam as if they all worked the same way.

They don’t all involve being cold-called by a scammer claiming to be from Microsoft, Cisco, BT, anti-virus companies and so on. Many of the reports I see nowadays come from people who’ve been lured by fake alert pop-ups into ringing a deceptive support desk number. Nowadays, there’s an accelerating trend among support scammers towards luring victims using pop-up ‘security alerts’ and fake system crashes. These invariably incorporate a phone number which is supposed to be to an ‘appropriate’ help line, thus trying to trick victims into making the initial telephone contact. For the scammer, this approach has an additional advantage: the scams can easily be changed to target users of OS X and iOS, Android and even Linux.

Figure 1: Linux with infected Windows firewall. Apparently …

Furthermore, as long as people aren’t aware of this variation on the scam theme, it can be implemented without the complicated social engineering sometimes involved in misrepresenting system utilities, or messing about with the command line after tricking the victim into allowing remote access. As far as the scammer is concerned, it’s better to get the individual to ring their helpline than for them to waste time cold-calling individuals who in many cases have been hearing the same rubbish for years, and will either ring off or try to waste their time. (I certainly don’t have a particular objection to wasting a scammer’s time, but I don’t particularly advocate it, either, unless you know exactly what you’re doing.)

Misused utilities

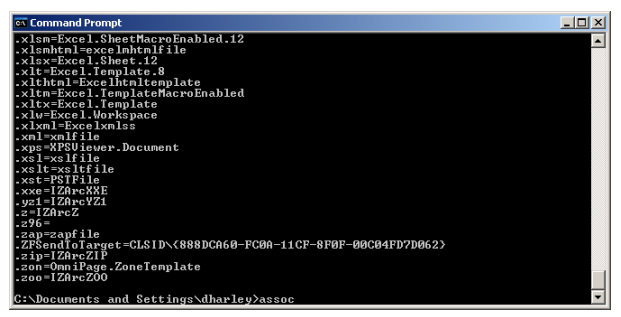

They do, however, still often include the use of ploys such as the deceptive use of Eventviewer and ASSOC, as described in a paper that Martijn Grooten, Craig Johnston, Steve Burn and I wrote for Virus Bulletin: these are used in order to convince the victim that the scammer really knows something about his (the victim’s!) PC. Utilities like EventViewer do have their uses, of course, for a tech looking for real problems. The trouble is, it’s easy for a scammer to misrepresent their output when talking to someone who isn’t knowledgeable about Windows internals.

Figure 2: ASSOC used to find the notorious CLSID

Imports, homegrown, and scam improvement schemes

They don’t all originate in India, though many clearly still do. Some of the reports I see are from people who’ve used a search engine in order to track down support for a specific product and have come across a fake site rather than the product’s real support team, and some of those reports concern companies in the US or Europe.

The same call centers that are peddling support scams are often peddling other scams such as dubious home improvement schemes, accident compensation schemes and PPI reimbursement fraud. (Which sound very strange when the scammer clearly knows very little about the legislation that applies in the country where the victim lives.) But some of the social engineering techniques used are common to most of these schemes: not least, pretending to represent a legitimate company or government department and to ‘solve’ an issue that doesn’t exist. Some scammers actually even claim to be offering recompense for money obtained fraudulently by support scammers, in the same way that 419 scammers sometimes claim to be offering repayment to 419 victims.

They may also be providing genuine support to the customers of legitimate companies – Symantec, Avast! and Microsoft are among the companies who’ve found their trust in an external contractor betrayed by the use of fraudulent sales techniques.

What to do?

Blog comments come up time and time again from people who’ve been sucked at least part way into the scam, asking ‘What should I do now?’ I’m not comfortable making some sort of blanket recommendation: it’s a question best answered on a case-by-case basis, though I’m afraid I can’t generally offer one-to-one support. For example, a comment on one of my articles on support scams was concerned that the (limited) access he apparently gave the scammer might have put him at risk of identity theft.

I can’t make any guarantees (reassuring or otherwise), of course, but this kind of scam isn’t usually reported as being directly associated with ID theft: they usually just want payment for their ‘services’. However, a recent Moneybox broadcast on leaks of TalkTalk customer information to scammers suggests that a customer was told ‘to download TeamViewer software, which was used to try to make a number of money transfers using third-parties’ credit card information’. And you may consider that to go beyond simply demanding money for deceptive services, though not necessarily any less fraudulent.

American readers can, however, check the FTC advice page for people who think their ID might be at risk.

Have I been hacked?

I often get requests for help from people who ran ASSOC, or Event Viewer or Netstat, and wonder if that could that have allowed the scammer to hack their systems.

I can’t give authoritative advice regarding a system I’ve never seen, but the answer is generally no. A scammer at the far end of a phone can’t do anything directly to a system if he doesn’t have remote access to that system. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t give a real support tech access your PC when you have a real system problem, if the nature of the problem allows. And utilities like EventViewer do have their uses, for looking for (some) real problems. Unfortunately, however, it’s easy for a scammer to misrepresent their output.

Remediation

Still, ‘what should I do?’ is perhaps a question most easily answered when the victim has actually given away pretty much everything the scammer has asked for.

- If you’re looking for information after you gave them access to your device, your system seems to be running more or less normally, and you haven’t restarted it, do that. (If you see one of those pop-ups that claim you have a virus problem and should call a help line, it will usually tell you not to restart your system. That’s usually because if you do restart, it will usually be obvious that you aren’t looking at a real, permanent problem.) Unfortunately, I can’t say for sure that there isn’t something malicious on a system I’ll never see, especially if you don’t use good security software. There is another caveat.

- Sometimes the scammer deliberately trashes the victim’s system, usually when the victim has allowed access but has decided not to pay up. The scammer may then delete files and/or lock the victim out of his own system. There are web pages around that offer a one(-ish)-size-fits-all approach to remediating this situation, but I’m not comfortable with that approach. Even well meant advice may actually make the situation worse in some cases. In any case, computer users who fall for this scam are not usually particularly tech-savvy, and it seems wrong somehow to expect them to undertake a potentially technically complex salvage operation on their own. Better to get professional help as soon as possible. One of my colleagues in North America suggests that if you’re an ESET customer – I suspect that most of the people who ask about this aren’t, though – that you power off (using the power switch, not a ‘polite shutdown’) and contact ESET Customer Care from another device. In the US you can do that via the web during business hours, or by email with this form. Customers outside North America may find their contact point(s) by browsing to http://www.eset.com/int/, then selecting the [International] drop-down menu in the upper right, selecting your region, etc., if needed. If you are not an ESET customer but are in North America, you might consider ESET Support Services.

- Run a reputable security program to check for anything unpleasant that they may have installed. I’m not going to claim that anti-malware always catches all malware, but the chances are good that they will detect programs that are unequivocally malicious and not fresh out of the developer’s lab. (Even brand new malware might, in any case, be blocked by a good security suite, even if it isn’t identified as a specific malicious program.)

- Change any passwords you’ve given them. If you gave them remote access, change any passwords to which they might have had access without your knowing. You can make life a little more difficult for the scammers if you made a note of their PIN/ID for the remote access utility they used, by reporting the misuse to the utility/service provider. AMMYY doesn’t seem to have an abuse report point as such, but LogMeIn does, and our friends at Malwarebytes say that if you contact TeamViewer’s support with the 9-digit code used by the scammer, it can be revoked. AMMYY does have advice on what to do if your scammer was using their service.

- Contact your credit card provider for their advice on stopping payment, getting money back, and if necessary, replacing cards. (Be aware, though, that there are actually scams that specifically make use of a phony security incident to try to get hold of your credit card for criminal purposes.)

- Contact law enforcement. The more law enforcement learns about current scams, the better the chances that action will be taken that reduces the scam’s effectiveness, though I don’t generally hold out much hope that the police can help as regards restitution and prosecution of the scammer in individual cases. However they can advise you on the possibility of identity theft, especially if you gave away personal information as well as financial information. You can also file a report with the FTC in the US and Action Fraud in the UK. Canadians can report fraud at the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre, and Australians can report it here. Don’t expect too much, though. In my experience, reporting scam calls is of limited use in remediating individual cases. No agency has the resources to follow up on every scam call, but the more information they have, the more effective they may be in pursuing persistent offenders.

The best way to counter the problem, though, is to forestall it by thinking ahead.

An ounce of prevention …

You can’t trust unsolicited phone calls: anyone can ring you up and say they’re calling from or on behalf of Microsoft (or anyone else).

Figure 3: Beware of the Bull

The circumstances under which some random caller can really know anything about your computer(s) are very rare. In general, if someone rings and says your PC is infected, it’s a scam. If he or she asks you for money to fix it, it’s always a scam. Or, at best, aggressive marketing, which is sometimes barely distinguishable from fraud.

If you (or your employer) have some sort of support contract that might just possibly involve someone calling you out of the blue about a security issue, make sure you have a way to verify their bona fides. If you see some sort of pop-up message or even a Blue Screen of Death including a ‘helpdesk’ telephone number, expect the worst. If it turns out you really do have a problem, find a more reliable source for a helpdesk number.

If you really think it might just be a genuine call, ring back to a known genuine number, and make sure the initial caller is really disconnected. (Here’s an extract from an earlier blog on another scam to explain why that’s important):

When you put your phone down, it doesn’t mean the line is immediately cleared. This may be changed at some point because of the ways in which this feature can be misused, but the system does have legitimate advantages: for instance, if the phone is put down on 999 call, it allows the operator to trace the call (for instance, where the caller has disconnected under duress). I can’t say if the same is true with 911 calls.

[There have even been reports of scammers using a recorded dialing tone so that the victim doesn’t realize the scammer is still on the line.]

If you need to look up a suitable support service, bear in mind that a search engine is likely to find links to scam pages as well as to companies offering genuine support services, including sites that have deceptive names suggesting links with Microsoft or Windows or Apple or Android. By sites, I mean not only company sites, but secondary sites such as Facebook pages and blog pages, where a great deal of unpleasant content of all sorts can be found lurking.

Many of the ‘what do I do now?’ questions I see seem to come from people who don’t have a regular security product installed, not even a free one. Given what I do for a living, you won’t be surprised that I strongly recommend using security software, even a free product, though a good for-fee product usually has the advantage of more reliable support. Don’t forget, though, that there is plenty of software passed off as a security product that ranges from useless to downright malicious. If you’re not sure which product to get (I could make a suggestion, but I’m not in marketing!), check out the mainstream security product testing organizations. I don’t always agree with the testing industry’s methodologies and claims, but reputable testers are not usually fooled into recommending fake products.

A good starting point would be the testers who are represented in AMTSO. (That’s the Anti-Malware Testing Standard Organization.) Testers and vendors that join AMTSO are usually trying to improve the accuracy of testing rather than just trying to manipulate it: participating testers do look at genuine products, and they do tend to conform to ethical guidelines.