Just over one year ago (November 2015), I released WMIOps, a PowerShell script that enables a user to carry out different actions via Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) on the local machine or a remote machine. WMIOps can:

- Start or stop a process.

- Return a list of all running processes.

- Power off, reboot, or log users off the targeted system.

- Get a listing of all files within a directory.

- Read a file’s contents.

- …and more.

As I continued to develop WMIOps and use it during Mandiant Red Team Operations, I realized that it has some of the same capabilities that are in Remote Access Tools (RATs). WMIOps’s capabilities were in a state of disparate functions, but if I wove what existed along with new functionality, I could create a RAT. After months of development and internal testing, I’m happy to publicly release WMImplant.

WMImplant leverages WMI for the command and control channel, the means for executing actions (gathering data, issuing commands, etc.) on the targeted system, and data storage. It is designed to run both interactively and non-interactively. When using WMImplant interactively, it’s designed to have a menu of commands reminiscent of Meterpreter, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: WMImplant main menu

Data Storage and Device Guard

After spending some time developing WMImplant, I ran into issues storing data on systems that used Device Guard, a Microsoft security feature added in Windows 10 and Server 2016. Even though this feature and these operating systems are not widely deployed today, I wanted WMImplant to support these systems since I expect Device Guard protected systems to become more common, especially at security-conscious organizations. Device Guard helps protect systems by employing (among other capabilities not detailed here):

- Code Integrity Policies – When deploying Device Guard, administrators will create a code integrity policy (CIP) that explicitly defines what is allowed to run on the protected system. This granularity can range from file hash, file name, publisher, both file name and publisher, and much more. Administrators can create the CIP from a gold-imaged computer. Administrators can further enhance their CIP by preventing applications that provide attackers the ability to bypass Device Guard’s protections from running. Finally, administrators can use Group Policy Objects (GPO) to enable Device Guard, preventing executables or select scripts from running unless explicitly allowed, per the CIP.

- PowerShell Constrained Language Mode – Device Guard auto-enrolls PowerShell into ConstrainedLanguage mode. Constrained Language mode restricts the cmdlets and data types that are allowed to run in PowerShell. In this mode, .NET methods are completely blocked unless they are an allowed data type.

On a Device Guard protected system, attackers cannot run custom executables, and the available PowerShell cmdlets are severely restricted. For example, simple functionality such as base64 encoding a string is not permitted within Constrained Language mode, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: PowerShell Constrained Language mode blocking base64 encoding

At first, I designed WMImplant to use the Windows Registry for data storage, as described in Matt Graeber’s WMI research. However, after discussing using the Windows Registry for data storage with Matt Dunwoody (a Mandiant coworker), he suggested, “Why not also use WMI itself for storage?”

This conversation led me to research using WMI for data storage. I found a proof-of-concept for creating custom WMI properties (Figure 3) in FireEye’s report on WMI Offense, Defense, and Forensics.

Figure 3: Sample code from FireEye report on WMI Offense, Defense, and Forensics

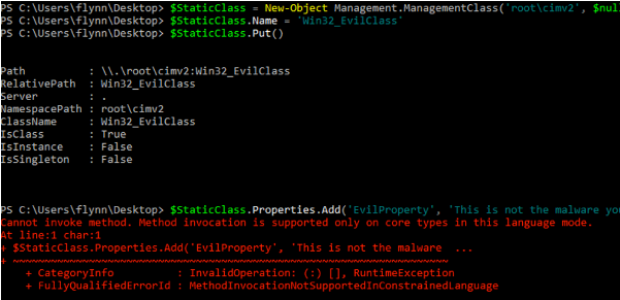

However, after testing this code on a Device Guard protected system, I discovered that this wasn’t permitted within Constrained Language mode, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Constrained Language mode blocking WMI property creation

After some additional research, I found that within Constrained Language mode, users are able to create custom WMI classes. But, as evidenced by Figure 4, WMI property creation is not allowed, so this wouldn’t work for data storage. Therefore, my next thought was to store data in an existing WMI property. In order to leverage an existing WMI property, a few conditions would need to be present:

- The property needs to be of type string.

- The property needs to be writable.

- The property needs to accept an arbitrary length of data.

- Modifications to the property need to not blue screen or degrade use of the targeted system.

- Most importantly, the property needs to be writable within Constrained Language mode.

I modified an existing PowerShell script to enumerate all WMI classes, find the properties of each class, check if each property is a string type, and determine if it is writable (the script is available here).

The script identified a list of candidate WMI properties, but for one reason or another, modifications to those that I initially tested resulted in “general failures”. Then, I came across a class I have not previously used: Win32_OSRecoveryConfiguration. This class has a property named “DebugFilePath”, which is the file path where Windows will place a memory dump after a computer failure, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Win32_OSRecoveryConfiguration’s DebugFilePath property

The DebugFilePath appears to only accept a file path, and the property should be limited to the length of a valid Windows paths (260 characters by default or 32k with LongPathsEnabled). In testing, however, I discovered that I could write an arbitrary string to the DebugFilePath property within Constrained Language mode without adversely affecting the targeted system. The final test was to determine how much data could be placed in the DebugFilePath property.

Figure 6: Data storage test within DebugFilePath

Figure 6 shows that the DebugFilePath property can store over 57 megabytes of data. This satisfied the data storage requirement for WMImplant, and future testing showed that the DebugFilePath property could store more than 250 megabytes of data. Additionally, using the DebugFilePath WMI property for data storage provides the side-benefits that it is easily retrievable and modifiable remotely.

This discovery shaped WMImplant’s command and control communications methodology. For commands issued by WMImplant that require data storage, the communication process is as follows:

- Remotely query and obtain the original value for Win32_OSRecoveryConfiguration’s DebugFilePath property.

- Use WMImplant to execute a command on the targeted system (such as ifconfig), encode the output, and store the encoded results in the DebugFilePath property.

- Remotely query the targeted system’s DebugFilePath over WMI to receive the encoded results.

- Decode the results and display them to the console.

- Set the DebugFilePath property on the targeted system back to its original value.

This methodology for command and control communications minimizes the amount of time that the WMI property is modified from its original state.

WMImplant Usage

I’ve developed WMImplant for both interactive and non-interactive use. Users also have the ability to change the user account that is authenticating to the targeted machine. As shown in Figure 7, users can issue the “change_user” command, provide the username and password to use, and then all future commands through WMImplant will authenticate with the provided credentials.

Figure 7: Changing the current user context within WMImplant

The easiest way to use WMImplant is interactively; however, that isn’t always possible. RATs such as Meterpreter or Cobalt Strike’s Beacon allow users to load and execute PowerShell scripts, but both of those tools require non-interactive use. That is, the tools accept a command to run, execute it, and return the results. They do not allow the user to interact with the command while running, however. WMImplant includes a built-in command-line generating feature specifically for this use case. To generate a command-line, start WMImplant and specify the “gen_cli” command.

After issuing the “gen_cli” command, the user will be presented with the normal WMImplant menu and asked for the command to be run. WMImplant will then ask for any required information for the command specified. Once the user has provided everything that’s required, WMImplant will display the command-line command to run in a non-interactive manner, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: “gen_cli” output

At this point, the user can load WMImplant within the RAT of choice, and copy and paste the command to run WMImplant non-interactively.

Another of WMImplant’s capabilities is the ability to run a PowerShell script on a remote machine and receive script output. This is performed through a multi-step process:

- The attacking system queries the targeted system’s DebugFilePath property to obtain its original value.

- The attacking system reads in the specified PowerShell script, encodes it, and stores it in the targeted system’s DebugFilePath property.

- WMI spawns a PowerShell process on the targeted system that reads the DebugFilePath property, and decodes the PowerShell script.

- The PowerShell process runs the user-specified function and stores the function output in a variable.

- The data in the variable is encoded and stored in the DebugFilePath property, and the PowerShell process exits.

- The attacking system makes an additional WMI query for the DebugFilePath value (currently storing the encoded data), decodes the data, and displays its contents to the console.

- The attacking system replaces the encoded data with the original DebugFilePath property contents on the targeted system over WMI.

This multi-step process is demonstrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Remote PowerShell execution

While I’ve only talked about a limited number of WMImplant’s features, others include:

- Setting/removing the “UseLogonCredential” Windows Registry value to enable credential caching.

- Uploading/downloading files.

- Enabling/disabling Windows Remote Management (WinRM) to remotely connect to and issue commands on a system using PowerShell.

- Identifying users who have logged in to the targeted system.

- Listing files by directory.

- Reading file contents.

- …and more.

I hope that WMImplant can help others as it has helped us on multiple assessments. If you notice any bugs, please let me know and I’ll be happy to get a fix pushed!